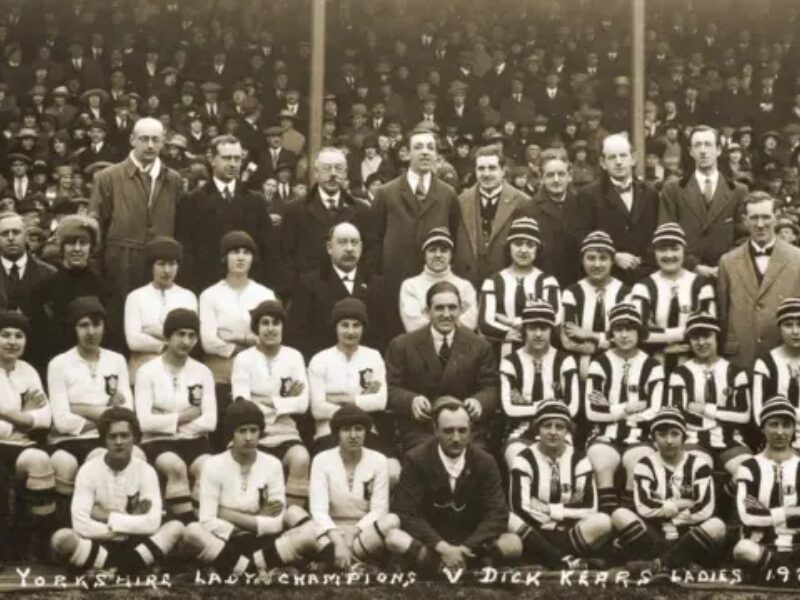

On Boxing Day 1920, more than 53,000 people passed through the turnstiles at Goodison Park to watch Dick, Kerr Ladies play St Helens in a charity match for wounded and unemployed ex-servicemen. Thousands more were locked out. The receipts exceeded £3,000, a sum that would now run into six figures. It was a record crowd for a women’s football match that would stand for more than nine decades. The scale of it was not a curiosity. It was a warning.

Women’s football had not crept quietly into public life. It had burst into it.

The game had always existed on the margins. Shakespeare alluded to women playing football in the sixteenth century. The first recorded women’s match took place in Edinburgh in 1881 and ended with pitch invasions and players escaping by horse-drawn bus. By the 1890s, clubs had formed in London, Grimsby, Preston and Edinburgh. The British Ladies’ Football Club drew more than 10,000 spectators to Crouch End in 1895, its players wearing bloomers and boots insisted upon by Lady Florence Dixie so that women could run properly. Even then, the spectacle unsettled. Crowds came. Authority bristled.

The First World War changed the conditions of possibility. With the men away, women filled factories, offices and transport roles. Football followed the factory floor. Informal kickabouts became teams. Teams became competitions. The Munitionettes’ Cup was contested in 1917. Blyth Spartans Munitionettes beat Bolckow Vaughan 5–0 in the final. Bella Reay scored a hat-trick. The most famous of the factory sides, Dick, Kerr Ladies of Preston, became a travelling institution. They played hundreds of matches, toured France and the United States, raised money for hospitals and charities, and drew crowds that matched and sometimes exceeded those of the men’s game. Lily Parr, 14 years old when she began, became their emblem. She could hit a ball hard enough to break a goalkeeper’s arm. She would score close to a thousand goals across three decades.

By 1921 there were around 150 women’s teams in England. Goodison Park was not an anomaly. Old Trafford, Deepdale, Stamford Bridge and Stockport all hosted women’s matches drawing tens of thousands. The women’s game was not tolerated as a novelty. It was attended as sport.

The reaction hardened as the war receded. Factories closed. Women were ushered back towards domestic life. Football, once framed as good for morale and health, was suddenly recast as dangerous to the female body. Doctors warned of strain. Commentators fretted about propriety. More troubling for those who governed the men’s game was money. Charity receipts raised by women’s matches were large and, increasingly, independent of official oversight. The crowds were not being funnelled into men’s fixtures. They were choosing something else.

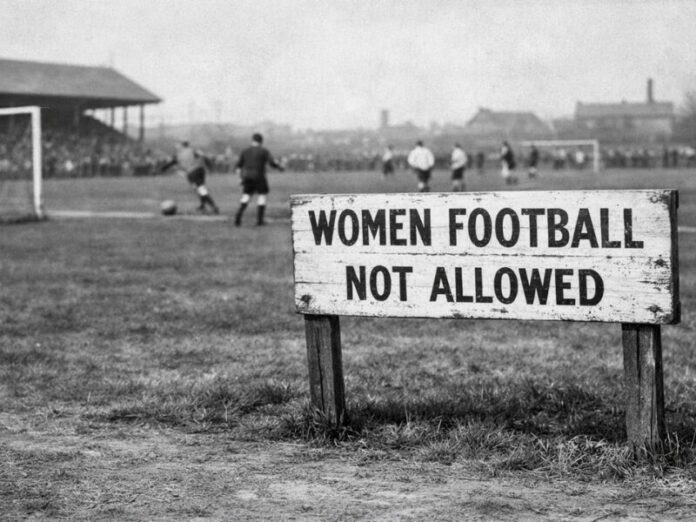

On 5 December 1921, the Football Association acted. It did not claim the power to stop women playing. Instead, it barred women’s matches from FA-affiliated grounds and asked its referees to refuse to officiate. The game, it declared, was “quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged”. Concerns were raised about expenses and the distribution of charitable funds. The practical effect was to strip women’s football of stadiums, officials and legitimacy in one stroke.

The decision was neither universally welcomed nor quietly accepted. Thirty teams met in Liverpool days later to form the English Ladies’ Football Association. A Challenge Cup was contested the following summer. Dick, Kerr Ladies toured North America. The game continued in parks, on rugby grounds, on borrowed pitches. But the mass visibility that sustains a sport had been cut off. Where tens of thousands had once gathered, a few hundred now stood along touchlines. The ban would last for 50 years.

The press revealed the temper of the moment. Some newspapers praised the FA as a wise authority suppressing an undesirable spectacle. Others quoted players who spoke with bewilderment and anger about being told the game they loved was no longer theirs to play. A dissenting voice within the FA noted that women’s football had raised vast sums for charity and played to a high standard. The decision went through regardless.

The effect was not simply a pause. It was a fracture in continuity. While men’s football professionalised and embedded itself culturally, women’s football was forced into an informal existence, kept alive by volunteers, factory teams and local clubs. Manchester Corinthians, founded so a scout’s daughter could play, toured Europe and South America in the 1950s and raised large sums for charity. The players washed in duck ponds because there was no running water. They won trophies abroad. They returned home to obscurity.

The ban was finally lifted in 1970. The following year, women could once again play on FA-affiliated grounds. A Women’s FA Cup began. England played Scotland in an official international. The Women’s Football Association expanded leagues, organised competitions and carried the sport through a decade in which it was still treated as an afterthought. The FA took formal control in the early 1990s. A national league followed. A professional structure arrived later. The Women’s Super League emerged, reshaped, and eventually stood as a fully professional competition.

The crowds returned slowly at first, then all at once. Wembley, which had hosted women as a warm-up act to men’s matches in the late 1980s, drew more than 70,000 for a women’s Olympic fixture in 2012. England’s European title in 2022 drew nearly 90,000 to Wembley and millions to television screens. By the middle of the 2020s, women’s football had become a commercial property measured in broadcast deals, sponsorship valuations and expansion fees. European Championships sold out. Investors bought stakes in clubs. Global revenues in women’s elite sport passed the billion-pound mark. What had been driven from the centre of the game was being priced back in.

The record set at Goodison in 1920 still stands as a reminder of what was interrupted. It took more than ninety years for a domestic women’s match in England to draw a comparable crowd. The intervening decades were not empty because interest was absent. They were empty because access had been withdrawn.