In 1967, women were not allowed to run more than 1,500 metres in sanctioned races. Marathons were for men.

Kathrine Switzer refused to share this sentiment. She was mocked, ridiculed and even her own coach did not initially believe it was possible for a female to run the course. Despite being told it would be impossible, at the age of 20-years-old, Switzer became the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon.

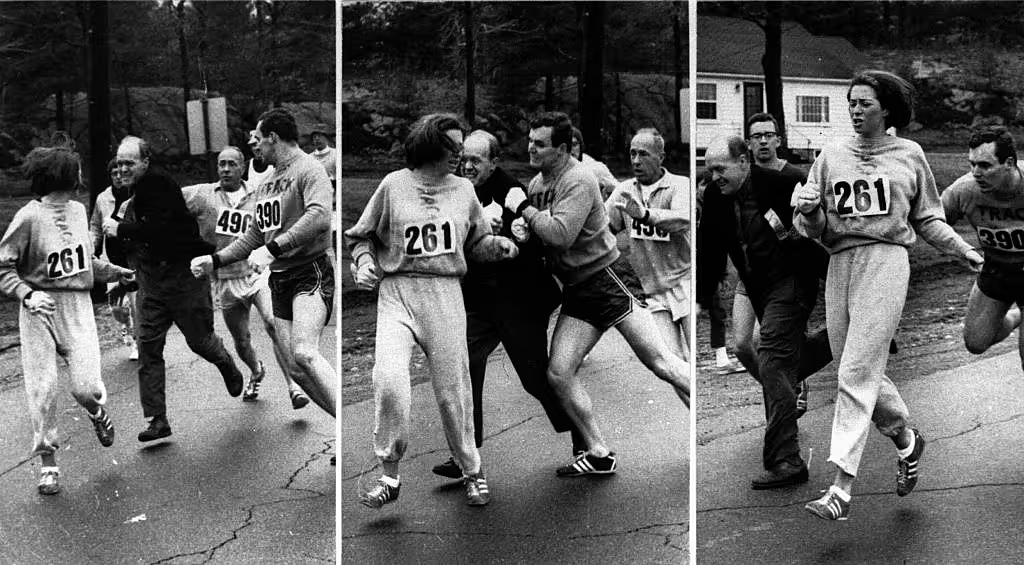

The rules did not explicitly prevent women from running, but it was tradition rigorously upheld by the organisers. The only way women could take part was to join the race from the side-lines and run without a numbered bib. Switzer slipped through the net by signing her name on the entry form for the Boston marathon by using her initials, KV Switzer. The organisers saw her name on the entry list and presumed she was a man. A mile and a half into Switzer’s first Boston Marathon, she was attacked by a race official. The official ran up behind Switzer, shouting and clawing at her sweatshirt. He was trying to pull off her bib with her race number on it. Switzer’s boyfriend barged the official off the road, a moment captured by a photographer from The Boston Globe that ensured its place in history. She finished the race with bloodied feet, badly shaken by her experience.

Little did Switzer know, her actions and what would follow would unintentionally start a social movement for equality in sport.

Switzer was a journalism student at Syracuse University. She had been running since school, but her university had no women’s cross-country team. She asked to run on the men’s track team but was informed that it would be against National Collegiate Athletic Association rules.

Instead, she was given the opportunity to train with the men’s team and the volunteer coach, Arnie Briggs. Briggs had run the Boston Marathon 15 times and spoke about this to Switzer on their runs.

"Without missing a beat," Switzer recalled, "my beloved Arnie Briggs said, 'A woman can't run the Boston Marathon. Women are too weak and too fragile for 26.2 miles. No dame ever ran no marathon.'"

Switzer was shocked but that did not change her mind. Briggs told her if she could prove to him in practice that she could run the 26.2 miles, he would be the first one to take her to Boston. The bet was on. After training hard for two-and-a-half months through Syracuse's brutal winter, the pair ran 26 miles during one session. They were going to Boston. Switzer paid the $2 entry fee, submitted her Amateur Athletic Union card and signed the form K.V. Switzer. To this day, she says she was not trying to avoid detection.

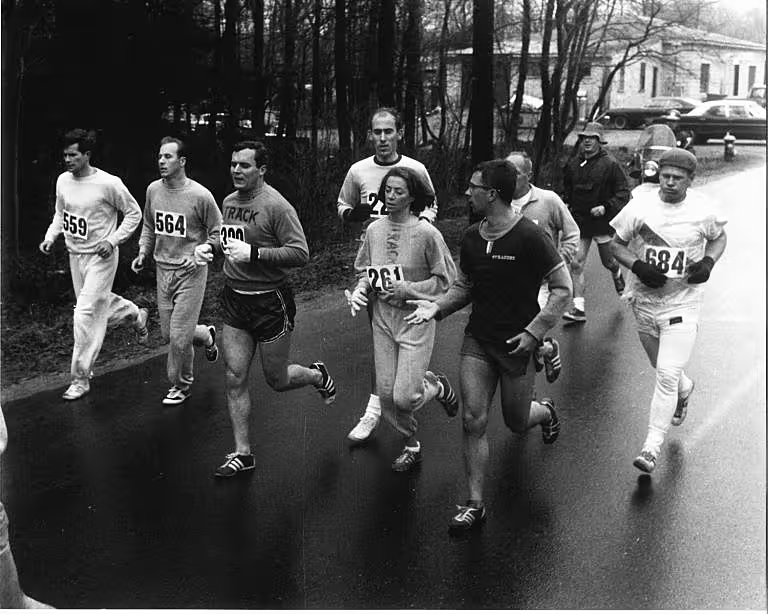

Briggs led a small group from Syracuse that included Switzer, Switzer's then-boyfriend and future first husband Tom Miller and another student runner, John Leonard. They drove through sleet and snow to Boston the night before and woke the day of the race, April 19, 1967, to more of the same. Switzer, wearing grey sweats and her hoodie up, pulled on black plastic garbage bags to help stay warm. It was a frenzied scene at the starting line, as officials with clipboards attempted to check the numbers of the 741 registered runners. The only woman with a bib number pulled up the garbage bag to reveal her number, 261, and was pushed along to the starting line.

The race began and the group settled into an easy pace. Switzer likened that first euphoric mile to a pilgrim making the journey to Mecca. When she threw off the trash bags and dropped the hoodie, revealing her shoulder-length chestnut hair, the runners around her starting smiling and nodding. There were however individuals who did not take this so well. John Semple and his co-race director, Will Cloney were waiting at the two-mile mark. Semple was a fixture in the Boston running community. While women had previously run the race on the side-lines, this was the first time one had obtained an official number. This incensed both race directors and they sought to take action.

What happened next was famously captured by The Boston Globe. Before cable television, the internet and social media, they captured the pivotal moment.

In the image, Will Cloney tried to block Switzer's path, but she eluded him. Semple, who managed to avoid Briggs (wearing bib No. 490), also tried to stop Switzer. Miller (No. 390), a 235-pound hammer thrower who was training to compete at the 1968 Summer Olympics, crashed into Semple's left shoulder.

Switzer, would not let herself be stopped. Thanks also to the help of Miller, she was able to free herself finish her race. She admits she fleetingly thought about quitting the race several times but persevered through the chaos to complete it. At one point she turned to Briggs and said, "I'm going to finish this race on my hands and my knees if I have to. Nobody is going to believe women deserve to be here if I don't finish this race."

Subsequently, Switzer was expelled from the athletic federation because she had run with men and without a chaperone. Yet her courage and perseverance changed the sport forever. Boston eventually allowed women to compete officially in 1972 thanks to her campaigning. Switzer went on to run the Boston Marathon eight times, recording her fastest time (2 hours, 51 minutes) in 1975. She ran the New York City Marathon four times, winning it in 1974, in 3 hours, 7 minutes.

Switzer pioneered the Avon Series of women's races, which culminated in the inaugural Olympic women's marathon event at the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles.

In 1972, the first year women were officially allowed to participate at the Boston Marathon, eight women (including Switzer) entered the race—and all eight finished. In 2019 a total of 11,982 women finished the race. All of this would not have been made possible had it not been for Kathrine Switzer.